脱贫|官方称贫困已成过去式

序: “一个国家对弱者的态度,其实反应着这个国家的文明程度.”

(选自The economist 2021年第一期)

Inequality is a different matter

不平等暂且先不讨论。

Early in december China announced that it had eradicated extreme poverty within its territory. This achievement is breathtaking in scale. By the World Bank’s estimate, some 800m people in China have escaped penury in the past four decades. It is a triumph for the ages, too, as state media have noted. Never before in the country’s history has destitution come anywhere close to being eliminated.

12月初,中国宣布已经在其境内消除了极端贫困。这一成就的规模令人叹为观止。根据世界银行的估计,在过去40年里,中国约有8亿人摆脱了贫困。正如国家媒体所指出的,这也是一个时代的胜利。在中国的历史上,从未有任何一个朝代近乎消除贫困。

One of the final places declared poverty-free is Ziyun, a county in the south-western province of Guizhou. “Speaking frankly, it’s a lie,” says Liang Yong, a gruff villager. The official investigation of Ziyun’s economy was, he says, perfunctory. Provincial leaders popped into his village, rendered their verdict that it had left poverty behind and then sped off. “It’s a show. In our hearts we all know the truth,” he grumbles.

最后一个宣布脱贫的地方之一是贵州省西南部的紫云县。"说白了,就是骗人的。"梁勇,一位粗犷的村民说。他说,官方对紫云经济的调查是敷衍了事。省里的领导到他的村子里蹦了一圈,做出了已将贫困甩在身后的结论,然后就开溜了。"这是在作秀。我们心里都知道真相。"他抱怨道。

But a hard-headed observer would side with the government. Things are undoubtedly difficult for Mr Liang. Pork is pricey these days, so he eats meat just a couple of times a week. After paying his two children’s school fees, he has little money left. To ward off the winter, he sits close to a coal-fired stove. He is poorer than many others in China, especially in its cities. He does not like to see victory over poverty being celebrated when he cannot afford proper medical care for his father, recently diagnosed with lung cancer. But the ability to scrape enough together for meat, education and heating marks Mr Liang as someone who has in fact left extreme poverty—a condition in which basic needs go unmet.

但如果是一个冷静的观察者,就会站在政府一边。对梁先生来说,事情无疑艰难。这些天猪肉价格昂贵,所以他每周只吃几次肉。给两个孩子付完学费后,他的钱已经所剩无几。为了抵御寒冬,他就坐在燃煤炉旁。在中国,他比许多人都要穷,尤其相对城里人来说。他不喜欢看到人们庆祝战胜贫穷的胜利,因为他无法为最近被诊断出患有肺癌的父亲提供适当的医疗服务。但是,梁先生有能力凑够肉食、教育和取暖的费用,这标志着他实际上已经摆脱了极端贫困——基本需求得不到满足的情况。

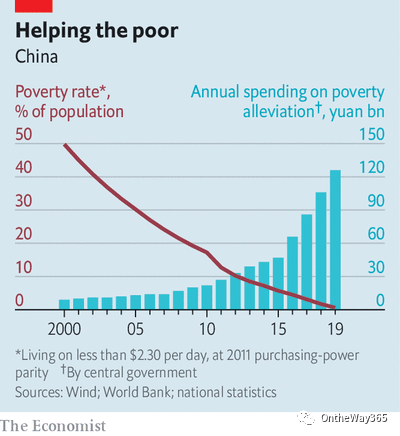

Sceptics understandably ask whether China fiddled its numbers in order to win what it calls the “battle against poverty”. There are of course still isolated cases of abject deprivation. China, however, set itself a fairly high bar. It has regularly raised the official poverty line, which, accounting for living costs, is about $2.30 a day at prices prevailing in 2011. (By comparison, the World Bank defines as extremely poor those who make less than $1.90 a day, as roughly a tenth of human beings do. Poverty lines in rich countries are much higher: the equivalent line in America is about $72 a day for a four-member household at 2020 prices.) In 1978, shortly after Mao’s death, nearly 98% of those in the countryside lived in extreme poverty, by China’s current standards. By 2016 that was down to less than 5% (see chart).

怀疑论者会问,中国是否为了打赢所谓的 "脱贫攻坚战 "而篡改数字。当然,仍然有个别极度贫困案例。不过,中国给自己设定了一个相当高的标准。它定期提高官方的贫困线,考虑到生活成本,按2011年的价格计算,每天约为2.30美元。(相比之下,世界银行将那些每天收入不到1.9美元的人定义为极度贫困,大约有十分之一的人是这样的。富裕国家的贫困线要高得多:在美国,按2020年的价格计算,一个四口之家的贫困线约为72美元)。在毛泽东去世后不久的1978年,按照中国目前的标准,农村近98%的人生活在极端贫困中。到2016年,这一比例下降到不足5%(见图)。

The government’s biggest contribution was to pull back from central planning and let people make money. It decollectivised agriculture, giving farmers an incentive to produce more. It allowed people to move around the country to find work. It gave more freedom to entrepreneurs. It helped by building roads, investing in education and courting foreign investors. Its goal was to boost the economy; alleviating poverty was a welcome side-effect.

政府最大的贡献是从中央计划经济中撤出,让人们赚钱。使农业非集体化,让农民有动力生产更多的东西。 它允许人们在全国各地流动找工作。它给企业家更多的自由。它通过修建道路、投资教育和吸引外资提供帮助。它的目标是促进经济增长;减轻贫困是一个受欢迎的附带效应。

The government’s approach changed in 2015 when Xi Jinping, its leader, vowed to eradicate the last vestiges of extreme poverty by the end of 2020. Officials jumped to it. They tried to encourage personal initiative by rewarding poor people who found ways of bettering their lot (see picture). They spent public money widely. In 2015 central-government funding earmarked for poverty alleviation was an average of 500 yuan ($77) per extremely poor person. In 2020 the allocation per head was more than 26,000 yuan (see chart).

2015年,政府的做法发生改变,其领导人习主席宣称要在2020年底前消除最后的极端贫困痕迹。官员们对此跃跃欲试。他们奖励那些找到改善命运方法的穷人,试图以此来鼓励个人主观能动性(见图)。他们广泛使用公共资金。2015年,中央政府的扶贫专项资金平均每个极度贫困者500元(77美元)。2020年,人均拨款超过26000元(见图)。

The imprint of the anti-poverty campaign is visible everywhere in Ziyun. The walls of government offices are covered in murals. One depicts a plant, labelled as the “roots of poverty”, being yanked from the soil. Slogans dot the main roads—some admirably simple (“Let farmers make more money”), others lofty (“To help people out of poverty, first help them become wise”).

在紫云,脱贫攻坚的印记随处可见。政府机关的墙壁上布满了壁画。其中一幅壁画描绘的是一株被称为 "贫困之根 "的植物被从土壤中拔出。标语点缀在主干道上——有些标语简单得令人钦佩("让农民多赚钱"),有些标语高大上("要想帮助人们脱贫,先帮助他们变聪明")。

One of the biggest challenges has been the terrain where the poor live. The 832 counties—about 30% of the country’s total—that were designated as poverty-stricken when Mr Xi began his anti-poverty campaign were all mainly rural. Most were mountainous or on inhospitable land. Officials used two basic approaches to help these counties. Both are visible in Ziyun.

最大的挑战之一是贫困人口居住的地势。习主席开始脱贫攻坚运动时,被定为贫困县的832个县--约占全国总数的30%--都以农村为主。大多数是山区或荒凉的土地。官员们采用两种基本方法来帮助这些县。这两种方法在紫云都能看到。

The first was to introduce industry—mostly modern agriculture. In Luomai, a village in Ziyun, the government created a 25-hectare zone for growing and processing shiitake mushrooms. About 70 locals work there. In the past their only options were either to migrate elsewhere or to eke out a meagre existence farming maize. But the shiitake are a cash crop, letting them earn about 80 yuan a day, a decent wage.

首先是引进产业--主要是现代农业。在紫云的罗麦村,政府建立了一个25公顷的香菇种植和加工区。大约70名当地人在那里工作。过去,他们唯一的选择是要么移居到其他地方,要么就是靠种植玉米来维持微薄的生活。但香菇是一种经济作物,让他们每天能赚到80元左右,这是份不错的工资。

There is an irony in this. In the 1980s China broke up communal farms, letting people strike out on their own. Now the government wants them to pool their resources again. Officials often describe it as turning farmers into “shareholders”. Residents get stakes in new rural enterprises, which, all going well, will pay dividends. Big outside companies are often placed in charge of the projects. The Luomai shiitake farm is run by China Southern Power Grid, a state-owned firm. But there is a risk that as the anti-poverty campaign fades away, some projects will fizzle.

这里面有一个戏剧化转变。上世纪80年代,中国打破了集体化公社,让人们自行出击。现在,政府希望他们再次集中资源。官员们经常把这描述为把农民变成 "股东"。居民在新的农村企业中获得股份,如果一切顺利,这些企业将分红。外来的大公司往往会被安排负责这些项目。罗麦香菇农场由国有企业中国南方电网公司负责运营。但随着脱贫攻坚战的淡化,一些项目有可能会泡汤。

The second approach to helping hard-up villages was more radical: moving inhabitants to better-connected areas. Between 2016 and 2020 officials relocated about 10m people. China has long moved people around on a huge scale to allow development—for instance clearing out homes to build dams. But in this case resettlement was itself the development project. The government concluded that it was too costly to provide necessary services, from roads to health care, to the most remote villages. It reckoned that moving residents closer to towns would work better.

第二种帮助贫困村的方法更为激进:将居民迁往交通便利的地区。在2016年至2020年间,官方搬迁了约1000万人。长期以来,中国一直在大规模地迁移人口,以实现发展--例如,为修建水坝而清理房屋。但在这种情况下,移民安置本身就是发展项目。政府认为,为最偏远的村庄提供必要的服务,从道路到医疗上来说,成本太高。他认为,将居民迁到离城镇更近的地方会更有效。

A collection of tidy yellow apartment blocks sits in the centre of Ziyun county. It is a settlement for former inhabitants of a poor village some distance away. A frequent problem after moving people into such housing is finding work for them. In this case, the government called on local officials to arrange jobs for at least one member of each household. At the gate to the new compound in Ziyun, women hunch over sewing machines in small workshops. A middle-aged resident says she could not handle that work, so officials gave her a job in a sanitation crew. She is pleased with her new surroundings. There is a good school just across the street, which is far better for her child.

在紫云县城中心,坐落着一批整齐的黄色公寓楼。这是距离这里较远的一个贫困村原居民的安置房。人们搬进这样的住房后,经常遇到的问题是为他们找工作。在这种情况下,政府号召当地官员为每户人家至少安排一名成员工作。在紫云新院的大门口,妇女们在小作坊里弓着背弄着缝纫机。一位中年居民说,她无法胜任这些工作,于是官员给她在环卫队里找了一份工作。她对新环境很满意。对面就有一所好学校,对她的孩子来说要好得多。

A bigger challenge is relative deprivation, a problem abundantly evident to anyone who has travelled between the glitzy coastal cities and the drabber towns of the hinterland. People may have incomes well above the official poverty line, but they can still feel poor. A recent study by Chinese economists concluded that the “subjective poverty line” in rural areas was about 23 yuan per day, nearly twice the amount below which a person would be officially classified as poor. That conforms with a standard used by many economists, namely setting the relative poverty line at half the median income level. It suggests that about a third of rural Chinese still see themselves as poor.

更大的挑战是相对贫困,这个问题对任何来往于光亮的沿海城市和内地单调乏味的小镇之间的人来说,是非常明显的。人们的收入可能远远高于官方的贫困线,但他们仍然会感到贫穷。中国经济学家最近的一项研究得出结论,农村地区的“主观贫困线”约为每天23元,几乎是官方贫困标准的两倍。这符合许多经济学家使用的一个标准,即把相对贫困线定为收入水平中位数的一半。这表明,大约三分之一的中国农村人口仍然认为自己是穷人。

If poverty is calculated this way it becomes almost impossible to eliminate, since the poverty line steadily rises as the country gets richer. But one virtue of using a relative definition is that it better matches the way people feel. China does not count any poverty in its cities because welfare safeguards supposedly help those without money. But workers who have moved from the countryside lack the right documentation for ready access to urban welfare. And for any city-dweller, support is meagre. In relative terms about a fifth of China’s urban residents can be classified as poor, according to a recent paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research by Chen Shaohua and Martin Ravallion.

如果以这种方式计算贫困,那么几乎不可能消除贫困,因为随着国家的富裕,贫困线会稳步上升。但使用相对定义的一个好处是,它更符合人们的感受。中国没有将城市中的贫困人口计算在内,因为福利保障制度理应帮助那些没有钱的人( 译者:如果谁被保障就假定他们非没钱的人? )。但是,从农村迁来的工人因为缺乏适当的证件,无法随时享受城市福利。而对任何城市居民而言,支持都是微乎其微的。根据陈少华和Martin Ravallion最近为国家经济研究局撰写的一篇论文,相对而言,中国约有五分之一的城市居民可以被归为贫困人口。

To reduce relative poverty, China needs different tactics from the ones used in its campaign against extreme poverty. It would have to redistribute incomes, for example by imposing heavier taxes on the rich and making it easier for migrants to obtain public services in cities—policies for which it has shown little eagerness.

为了减少相对贫困,中国需要采取与脱贫攻坚运动不同的策略。中国必须重新分配收入,例如对富人征收更多的税,让移民更容易获得城市的公共服务----中国对这些政策并不热衷。

On the streets of Guiyang, the booming capital of Guizhou, hardship is still a common sight. Men walk with straw baskets strapped to their backs, looking for work as load-carriers. Zhou Weifu, a porter in his 50s, scoffs at the suggestion that poverty is over. “What kind of work is this? I can barely make any money,” he says. China has every right to be proud of its victory over dire poverty. But officials would be wise to keep their celebrations muted.

在迅速发展的贵州省会贵阳街头,艰苦的景象依然随处可见。男人们背着背篼走在路上,寻找搬运工的工作。50多岁的搬运工人周维福对脱困的说法嗤之以鼻。"这算什么工作?我几乎赚不到钱,"他说。中国完全有权为自身战胜极度贫困而感到骄傲。但是,官方最好保持低调的庆祝。

This article appeared in the China section of the print edition under the headline "The fruits of growth"