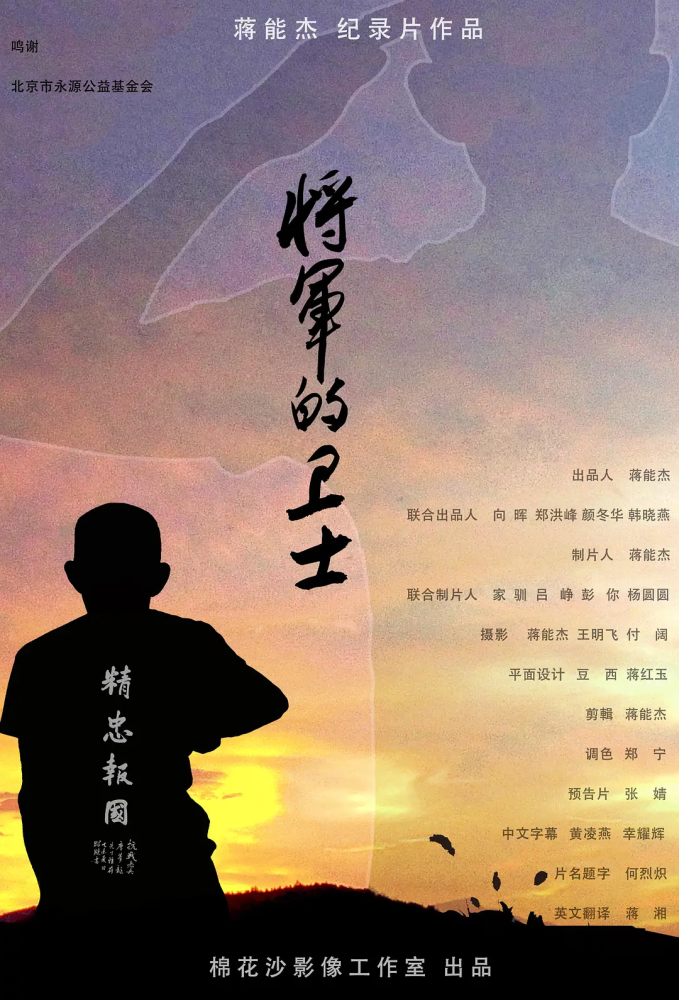

“The General’s Guard”: The Humiliation and Hardship of a War Hero Beyond the Battlefield

Recently, I watched the documentary The General’s Guard, which depicts the post-war experiences and later-life struggles of Tang Menglong, a Nationalist hero of the War of Resistance Against Japan (1937-1945). After watching this film, I felt compelled to share some thoughts on the history and realities it reflects.

The documentary’s protagonist, Tang Menglong, once served as the bodyguard of Nationalist General Song Xilian. In 1937, after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, Tang joined the Nationalist army to resist the Japanese invasion and defend his homeland. Alongside General Song and other comrades, Tang endured the brutal war from 1937 to 1945, even sustaining injuries in the line of duty. Through their sacrifice of blood and flesh, they safeguarded the nation and its people. After the war, Tang accompanied Song Xilian to Xinjiang. Like the millions of Nationalist soldiers, Tang Menglong was a celebrated hero of the victorious Allied forces, earning respect from the Chinese people and the global anti-fascist community. A bright future seemed to await him.

However, the outbreak of the Chinese Civil War shattered those expectations. Within just four years, the Chinese Communist forces defeated the Nationalists, and Song Xilian was captured in southwestern China. As for Tang Menglong, who had been demobilized and returned to his hometown, he, along with his wife and children, endured decades of political persecution under the Communist regime, especially during the harrowing years of the Cultural Revolution. This grim reality was something unimaginable even for Nationalist soldiers who had either surrendered or retired to civilian life.

The “New China” that emerged under Communist rule refused to acknowledge these anti-Japanese heroes. On the contrary, Nationalist soldiers—members of the “National Revolutionary Army,” also called the “Kuomintang Army” depending on one’s political perspective—were vilified as part of the “reactionary Kuomintang.” Regardless of their wartime contributions, they were deemed enemies. During Mao Zedong’s era, the prevailing narrative focused on class struggle and opposing Nationalist rule; contributions to the anti-Japanese war were downplayed or dismissed entirely. (During this period, the regime didn’t commemorate the War of Resistance or events like the Nanjing Massacre and even supported Japan’s anti-American stance.) Simply being affiliated with the Nationalist government or military was considered an unforgivable crime—even though Mao himself had once held a senior position in the Kuomintang during the First United Front.

During the “Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries” in the early 1950s, many heroes of the Xinhai Revolution and the War of Resistance were executed by the Communist regime. Others were sent to impoverished and remote regions for “labor reform.” In the Anti-Rightist Movement, numerous intellectuals who had participated in the resistance were denounced and exiled. During the Great Famine, many Nationalist soldiers and intellectuals who had survived the horrors of the Japanese invasion perished from starvation in labor camps. Later, during the “Four Cleanups Movement,” even Communist members with past Nationalist affiliations were scrutinized and persecuted. These political campaigns and disasters destroyed the lives, careers, and even the very existence of countless heroes of the resistance.

Tang Menglong was one of the few who narrowly escaped death during these tumultuous times. But an even greater ordeal awaited him during the Cultural Revolution, which the Communist Party itself has since acknowledged as a “catastrophe.” During this decade of chaos, Tang and his family were repeatedly humiliated and beaten by Red Guards. Their neighbors, who had joined the Red Guards, not only harassed and oppressed him but even attempted to kill him. Tang survived by fleeing to the mountains, where he hid while his family secretly brought him food. Even in their later years, Tang and his wife remained haunted by these experiences, still fearful of their former Red Guard neighbors.

Tang Menglong’s wife was a Communist Party member, a textbook example of a “progressive youth” during her early years. She had once disregarded her family’s interests to provide food and money to the struggling Communist forces. However, even her sacrifices did not spare her from the Cultural Revolution’s fanatical Red Guards. She was persecuted to the point of lifelong disability and had to rely on a cane for the rest of her life. Her tragic fate mirrored that of many Communist officials, from high-ranking figures like Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping to countless grassroots Party members. The plight of Tang Menglong and his wife serves as a microcosm of what both former Nationalists and Communists endured during Mao’s era—a testimony to the survivors.

During Mao Zedong’s roughly 30-year rule, Nationalist soldiers who fought in the War of Resistance Against Japan lived through a hellish existence. Many had already died, and those who survived suffered relentless humiliation, as if, to borrow a phrase, they were “enslaved by the hands of others, slaughtered alongside cattle and horses.” Their dignity was stripped away, and their physical and mental suffering compounded by countless abuses. Many could no longer bear the torment and chose to end their own lives. Tang Menglong and his wife also contemplated suicide but ultimately decided to persevere for the sake of their children, unwilling to leave them uncared for.

Yet these wartime heroes should have been revered by the people they fought to protect. In a peaceful era, they could have continued to serve as vital pillars of national defense and reconstruction, enjoying generous compensation and social care. They might have been honored with medals, invited to schools and government ceremonies to recount their wartime stories, and basked in flowers and applause. If circumstances had been different, they could have lived their later years like Nationalist veterans in Taiwan or Allied forces such as U.S. and British soldiers, receiving substantial welfare and dedicated personal care.

However, history’s complex interplay of coincidence and inevitability, both domestically and internationally, altered the fate of the Chinese people and that of these Nationalist veterans. Instead of receiving recognition, they were plunged into a nightmare. Their dignity and honor were destroyed, along with their basic human rights and reputations. Their monumental contributions were erased, and they were burdened with stigmas like “reactionary Kuomintang,” “landlord/exploiter class,” or “zaoyangjun” (a pejorative term for the Nationalist Army during the Civil War and Mao era).

The experiences and stories of countless Nationalist soldiers—their heroic deeds and the profound emotions and reflections born of war—were enough to inspire a thousand Band of Brothers, The Old Gun, or Saving Private Ryan-like films. Yet these narratives have been irretrievably lost as these veterans were silenced by persecution, driven mad, incapacitated by age or illness, or passed away. Even precious wartime relics were destroyed or lost. For example, Tang Menglong’s certificates and badges honoring his wartime achievements were confiscated during raids or buried underground, only to rot away. Many invaluable artifacts of the resistance, comparable to the Sichuan Army’s “Death Flags” or the wooden carvings of Guangxi Student Army’s pledge to “one day raise the Blue Sky, White Sun flag atop Mount Fuji,” were permanently and irreversibly destroyed.

When Mao Zedong passed away and Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping rose to power, surviving resistance veterans no longer faced brutal persecution for their Nationalist affiliations. However, their honor was not fully restored. Even when they were “rehabilitated,” this only meant an acknowledgment that their persecution was unjust; it did not mean full recognition of their status as anti-Japanese war heroes. Later policies, such as the One-Child Policy and other harmful reforms, continued to wreak havoc on the lives of resistance veterans and the Chinese people as a whole, though the scale of suffering was far less than during Mao’s era. Poverty also continued to plague these wartime heroes and their families.

Another critical factor suppressed the memory and commemoration of these veterans and the War of Resistance itself: the 1980s and 1990s were an era of “Sino-Japanese friendship.” At that time, Japan was an economic powerhouse with advanced technology and immense national strength. Its per capita GDP was over 30 times that of China, and its total GDP was more than five times greater. Due to poverty, China’s urgent need for foreign investment and technology, and its opposition to the Soviet Union (a factor behind Mao’s earlier pro-Japanese stance), the Chinese government pursued a conciliatory policy toward Japan. This “friendship” was achieved at the expense of tolerating Japanese right-wing efforts to deny or glorify its wartime aggression, including visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. When Hirohito, Japan’s primary World War II war criminal, died, China sent a high-level delegation to pay respects. Emperor Akihito even visited China in 1992 and was warmly welcomed.

In this context, both the War of Resistance Against Japan and the soldiers who fought in it were handled with restraint and subdued recognition by both the Chinese government and the general public. Faced with the flood of Japanese goods, culture, and people—ranging from tourists to high-ranking Japanese expatriates enjoying “privileged treatment” in China—veterans of the war, along with survivors of Japanese atrocities, felt deeply conflicted. It is reminiscent of a scene from the anti-Japanese film Encirclement, where Erxi, a villager who had fought the Japanese alongside his brother after losing his family, sits in a daze during his later years, watching a Japanese-made SUV drive past the same dilapidated village he has lived in for decades. Similarly, as recalled by Chinese-Canadian writer Tao Duanfang, a Nationalist veteran who had fought in the Battle of Shanghai in 1937 fainted in the 1980s upon seeing Japan’s national flag displayed at an exposition—overwhelmed by either rage or shock.

Although some efforts were made to commemorate the war, such as the production of films like The Battle of Taierzhuang, the degree of emphasis given to the conflict was far less than its monumental historical significance and impact warranted. It also did not reflect the immense suffering of the Chinese people during the war. As a result, the War of Resistance and its heroes faded into the background in the face of contemporary realities. Many veterans, by then elderly, passed away quietly and unacknowledged.

When comparing the postwar experiences of Japanese soldiers to those of Chinese veterans, the contrast is deeply sobering. After Japan’s defeat in 1945, its economy collapsed, and both soldiers and civilians lived in poverty for a time. Many soldiers who had committed atrocities faced the threat of accountability and trials. However, following the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the geopolitical calculus of China (both the Communist and Nationalist sides), the U.S., and the Soviet Union shifted to prioritize Japan’s alliance over justice for its war crimes. As a result, the U.S. provided extensive support to Japan, allowing its economy to recover rapidly without fully eradicating the remnants of militarism. By the 1960s, many former Japanese soldiers who had participated in the invasion of China—including those responsible for arson, murder, and sexual violence—were already receiving “consolation payments” from the Japanese government.

By the 1970s and beyond, most surviving Japanese veterans enjoyed substantial pensions and an enviable standard of living. Many Japanese citizens regarded them as national heroes who had safeguarded Japan and restored its postwar dignity. This reverence was epitomized in 1974 when Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese soldier who had waged guerrilla warfare in the Philippines for decades and only surrendered that year, was welcomed home by throngs of flag-waving Japanese citizens. Meanwhile, most members of the Imperial Japanese Army who had invaded China spent their later years in relative affluence, with access to quality care during illness and old age, and often lived long, comfortable lives.

In stark contrast, the fate of China’s righteous and heroic soldiers is all the more infuriating and heartbreaking. The stark disparity raises profound questions about who the true victors and losers of the war were—China or Japan.

World War II is widely recognized as a decisive event that reshaped humanity’s destiny, determining whether the world would move toward independence, freedom, peace, and prosperity, or remain under fascist tyranny, racial oppression, and the destruction of human dignity. Fortunately, with the courageous efforts of the international anti-fascist coalition, including China’s soldiers, justice triumphed over evil. Yet, Chinese veterans of the War of Resistance—who were instrumental in ushering humanity into an era of unprecedented civilization, peace, and prosperity—did not enjoy the fruits of their victory. Instead, they endured conditions more brutal than wartime, in an environment more impoverished and backward than the one they fought to protect, suffering relentless hardship and humiliation.

It was not until the last few years of the 20th century and the early 21st century, under the leadership of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, that China gradually began to mention the War of Resistance Against Japan, and the veterans of the war received some attention and care. However, by this time, most of the veterans had already passed away, and only a few remained. By the period from 2010 to 2015, when the War of Resistance began to receive broader recognition and was elevated to a noble status, very few veterans were still alive, and the vast majority had already passed on. The deceased veterans, like Tang Menglong, generally lived in poverty and humiliation, and did not live to see the day when they were officially recognized as national heroes and contributors to the nation. Many of them died by suicide under unjust circumstances. Even now, despite the more grandiose commemoration of the War of Resistance, it cannot compensate for the tragedies that have already occurred or the consequences that have been caused, leaving only everlasting regret.

This is the bitter consequence of the actions of the Chinese Communist Party during the Mao era. The achievements of eradicating the anti-Japanese Nationalist forces (during the Cultural Revolution, even the CCP’s own anti-Japanese efforts were erased, and anti-Japanese heroes like Peng Dehuai, who commanded the Hundred Regiments Offensive, and the survivors of the five warriors from Langya Mountain were not spared from persecution), and the brutal suppression of the Nationalist forces who fought in the War of Resistance, destroyed both people and memories at a time when the War of Resistance and its heroes should have been celebrated. This damage is irreparable.

Not only were veterans like Tang Menglong treated so tragically, but survivors of various massacres during the War of Resistance, comfort women, and forced laborers also suffered numerous injustices after the founding of the Communist government. Those who survived remained low-key. Their efforts to defend their rights and seek justice from Japan were suppressed by the Communist Party. By the time the Communist government began to support such rights movements, most of the victims had already passed away, and the survivors still did not receive adequate recognition or care. In contrast, victims of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki received global attention, with various speeches and even a Nobel Peace Prize awarded to related organizations in 2024. This comparison highlights the bitter reality that, in this context, China appears to be the defeated country, while Japan is regarded as the victor. The greatest regret for the survivors of the War of Resistance is that the memories of most of them have been erased from history, with no preservation or transmission of their stories.

What has been destroyed is not just the grand collective memory of the nation, but also the lives and happiness of individual people. The experiences that Tang Menglong recalls in the documentary, where he was repeatedly persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, are real examples of how basic human dignity, body, and spirit were damaged. These persecutions had an indelible impact on his entire family, leaving visible and invisible scars on his children, who were still young at the time. The long-term poverty induced by the political environment and the family’s vulnerable position in their community continued to trouble Tang Menglong’s family even to this day.

During the War of Resistance, Tang Menglong was fearless in sacrificing himself, bravely fighting the enemy, and defending the country. But in the decades that followed, he was powerless even against malicious neighbors, unable to protect his family, enduring humiliation and having to quietly tolerate it. After enduring various humiliations, Tang Menglong transformed from a spirited general’s guard into a cautious, low-key elderly civilian. Yet when discussing the War of Resistance or singing Nationalist military songs, his heroic nature still shines through. Though he was reserved when talking about events after 1949, he still courageously shared many of his experiences, without numbness or loss of courage.

In his later years, Tang Menglong, along with his middle-aged son, finally gathered the courage to demand an explanation from the old Red Guard neighbors who had once tormented them, following the national commemoration of the War of Resistance and the social recognition of Tang Menglong. The defense given by the former Red Guards, like many others—those who had betrayed or harmed people during the Cultural Revolution—was to justify their actions by citing the unavoidable environment of that time. But any evil is carried out by specific people, many of whom were active participants. Even those who merely followed orders were guilty of what has been described as “the banality of evil.” They may have had their own justifications, but if we forgive them, where does that leave the victims? Without distinguishing right from wrong, social morality decays further, and in the confusion between good and evil, more harm can emerge.

The changes in Tang Menglong’s family circumstances were also shaped and determined by national policies and the broader environment. During the thirty years when Satan-like figures were in power, Tang Menglong’s family could only struggle in despair, with life and death in the hands of fate and unable to resist, like fish on the chopping block, at the mercy of others. During Deng Xiaoping’s era, although there was a glimmer of hope and the end of the “untouchable” status, they could only live quietly, too afraid to demand justice. It was only when a new era came that they received some recognition in terms of spirit and reputation. Every individual, under the pressure and manipulation of Leviathan and the shaping of the broader environment, had little autonomy. Various harms, tortures, and the terrifying shadow of fear made people hesitant to resist and claim their rights, even when they were safe. Tang Menglong did not actively fight for compensation and treatment during the 1980s’ “rectification of wrongs” because of his fear that the Mao-era terror might return. The fear of tyranny caused people to “voluntarily” give up their rights, which in itself is a crime of tyranny.

Although after 2013, Tang Menglong’s family finally gained some societal recognition and widespread respect, the mundane matters of life, such as food, medicine, and the inevitable passage of time, continued to trouble him and his family. Interviews and watching military parades brought temporary joy, but everyday life was marked by long-lasting desolation. Family conflicts and the sorrow of having no filial children by the bedside during long illnesses were also present in Tang Menglong’s family. Even great men and immortal achievements cannot offset the hardships of life.

The level of care that society shows to veterans like Tang Menglong is uncertain, partly genuine and partly a facade. Tang Menglong’s daughter’s experience of being rejected when seeking help from charity organizations reflects that the halo of being a war veteran does not bring much tangible help. In China, poverty is still widespread, society remains fragmented, and many public welfare organizations are ineffective. From the Communist Party’s high levels to grassroots organizations, how many really admire his achievements in fighting the Japanese, and how many are simply exploiting him?

Tang Menglong’s achievements were during the War of Resistance Against Japan, but the humiliation and suffering he endured occurred mainly in the decades after the war, in the post-war years. In other words, it was another war outside the war of resistance—a continuous tragedy of fratricidal conflict, a one-sided massacre of unarmed fellow citizens by those in control of the state’s machinery of violence. This is even harder to understand and accept than being tortured by the enemy or dying on the battlefield. In his later years, Tang Menglong refused to wear the medal given to him by the Communist Party/China’s Central Military Commission, which can be seen as his final form of resistance—rejecting and “not cooperating” to denounce the persecution and trauma of those decades that should not be forgotten.

In 2017, Tang Menglong completed his tortuous life and bade farewell to a world that had granted him high honors but also caused him immense suffering. His family continued to live in the mixed joys and sorrows of everyday life.

Tang Menglong was unfortunate—he endured the Japanese invasion of China in his youth and saw his homeland shattered; after 1949, he faced numerous calamities, being harmed by his own countrymen, and his later years were not particularly happy. However, Tang Menglong was also fortunate, for many more Chinese people and many more veterans of the War of Resistance were even more unfortunate, suffering greater persecution and injustice, dying earlier, and quietly aging without recognition. Tang Menglong lived to see the time when the government and society finally recognized him, and he was able to be interviewed and filmed, speaking out the words he once could not speak and could not make known, leaving the world with some images and memories.

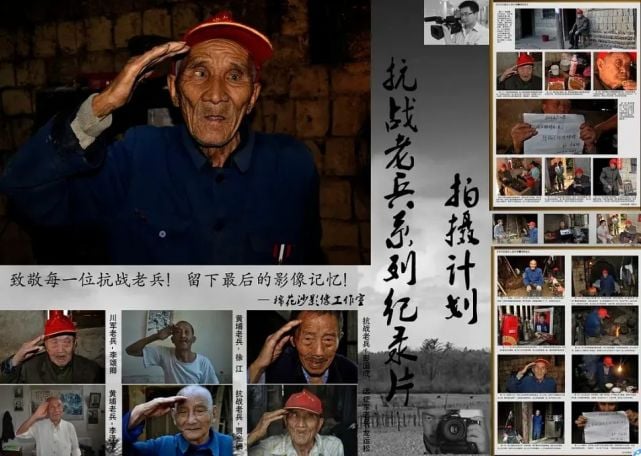

Not only Tang Menglong, but in recent years, most of the veterans of the War of Resistance, survivors of the Nanjing Massacre, survivors of comfort women, and others have passed away, with only a few remaining. The echoes of an era, which should not have ended yet (because there are still many untold stories, unresolved issues, and justice yet to be achieved), have already irreversibly faded into permanent silence.

We thank those who care for the veterans of the War of Resistance, for capturing the last living witnesses of that tragic era in the fleeting passage of time, leaving behind images and sounds, allowing history to be remembered even after it has passed, and allowing the lives that have passed away to live on in another way.